I would be remiss if I didn’t mention my current exhibition in the National Museum of American History before the New Year begins! It so happens that 2014 was the fiftieth anniversary of the Museum, and the exhibition which I curated, “Continuity and Change: Fifty Years of Museum History,” was one of four special exhibitions dedicated to the celebration of that anniversary. Although “Continuity and Change” is intended as a “permanent” or perhaps semi-permanent display, researching the history of NMAH reminded me just how ephemeral assertions of permanence can be in the museum world! The best example of this is the current name of the Museum, the result of an official change in 1980, whereas the building had opened to the public in 1964 as the Museum of History and Technology. One of the other anniversary exhibitions, “Making a Modern Museum,” curated by Dr. Arthur Molella, emphasizes how the original name and emphasis of the Museum were partly rooted in the competitive spirit and mentality of the Cold War, and that a thinly veiled agenda was to glorify the history of American technological might in contrast with that of Communist nations.

On the other hand, the name reflected the curatorial organization of the Museum and its component collections. We did have world-class collections of technological artifacts, and some of these collections and related exhibitions were international in scope. When I worked in the Photographic History Collection, we tried to document the entire history of photography, including technology and art, regardless of the national origin of the artifacts and photographs. In displays of photographic equipment (such as cameras) or photographs, we acknowledged nationalities in a neutral manner without emphasis or conclusions. Of course, the Museum tended to accumulate more American items than non-American, for a variety of reasons—not the least of which was sheer convenience. Before I moved from Photographic History to the Archives Center I was devoting special attention to the acquisition of European and Japanese photographs.

The name “History and Technology” indicated what I call the “bifurcated” nature of the Museum. It was like two museums in one. If you entered the building from Constitution Avenue, you soon saw the central object, a Foucault pendulum in motion. This was a powerful motif for the entire first floor, symbolizing science and technology—not only an overview of the history of physics and chemistry, but also specific technologies, including “heavy industry” and engineering, such as petroleum production, nuclear energy, bridges and tunnels, and transportation, such as railroads, plus lots of “old cars.” And would you believe there was also a “permanent” exhibition on the history of Arab pharmacy?

If you entered the second floor from the Mall entrance, you were immediately confronted by the enormous Star-Spangled Banner, hanging vertically on the far wall. This iconic patriotic artifact symbolized American history, and the first floor was indeed devoted to American political history and cultural history (including the popular First Ladies’ gowns exhibition in its various iterations, which arguably combined political and cultural history). The third floor sometimes seemed like a hodge-podge, with space allocated to American military history, plus exhibit halls on numismatics and postal history, textiles, ceramics and glass, graphic arts, photography, etc. These displays were related because they represented technologies used to produce objects embodying visual communication, aesthetic design, or art.

One momentous event in the history of the building was a major fire on the third floor in 1970 (caused by a malfunctioning computer on display), but I couldn't work that story into my script, nor could I locate appropriate documentary photographs. The Museum was very lucky: no collection artifacts were destroyed or seriously damaged in the fire, and a special infusion of Congressional funds for repairs was sufficient to complete the Hall of Photography, the Hall of Graphic Arts, and a Hall of News Reporting between them. The postal history display was cleverly linked to Graphic Arts via a Benjamin Franklin period setting, since Franklin was both a printer and postmaster. These adjacent "permanent" exhibitions formed a series on the theme of communication--although this may not have been obvious to the casual visitor.

![]() |

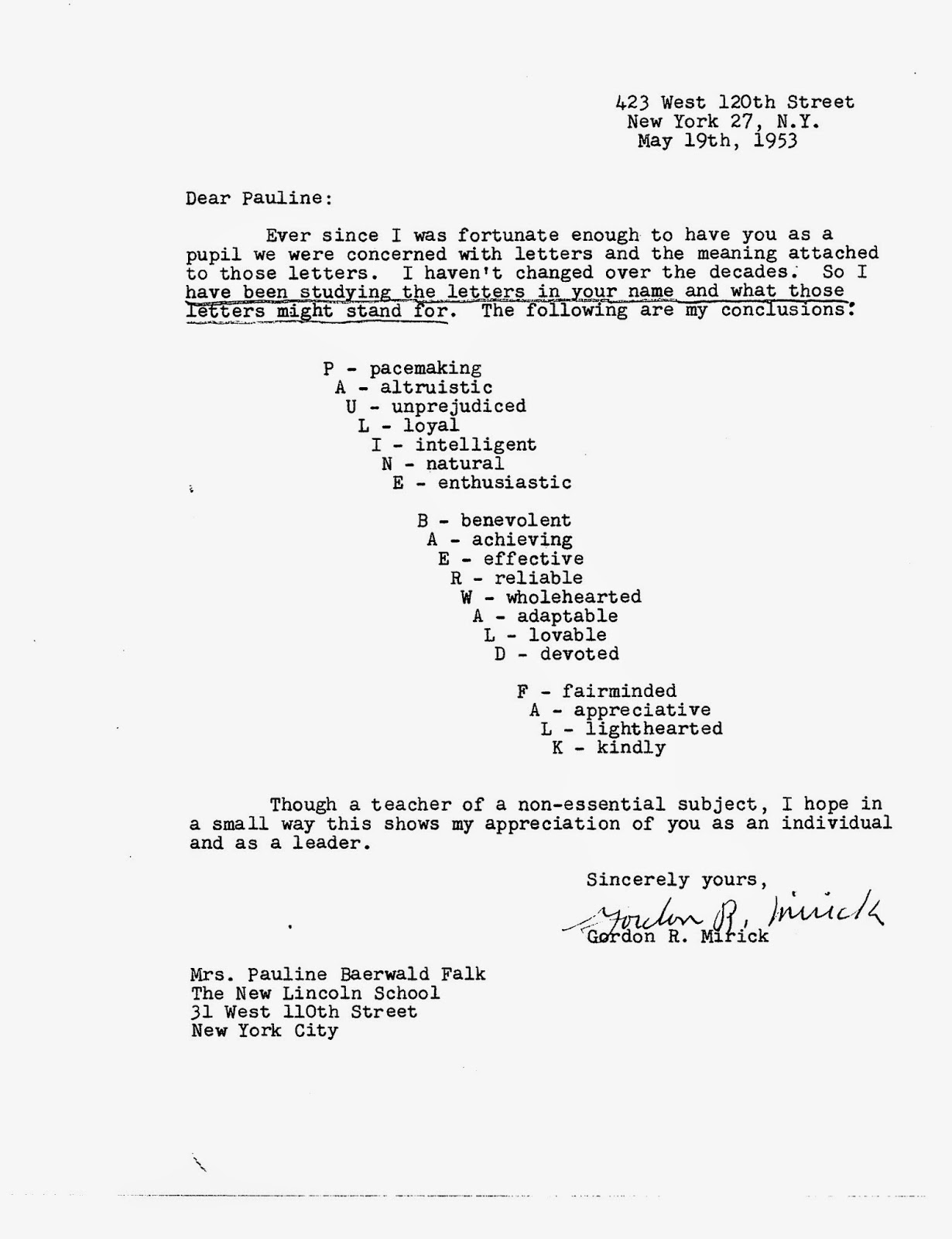

| "1876: A Centennial Exhibition," a re-creation of the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition in 1876, in the Arts and Industries Building,, opened May 10, 1976. This section displays industrial wares by such companies as Reed & Barton, Doulton & Co., and Meriden Britannia Co. Photographer unidentified. SI Archives, Historic Images of the Smithsonian. |

Although a variety of factors led to the Museum’s change of name and direction, one of the strongest was the influence of the Bicentennial of the United States in 1976. A number of special exhibitions sponsored by the Museum both celebrated and explored the history of this country. They required new directions, or at least new emphases, new collecting initiatives, and new programs. As I recall, virtually the entire staff of the Museum was actively engaged in some aspect of planning one or more of these exhibitions for many months. One of these exhibitions was not even located within the museum building proper, but occupied essentially all the display space in the Arts and Industries Building across the Mall. In my exhibition I included photographs of that exhibition, "1876," which celebrated the Bicentennial through re-creating the look and feel of the Centennial of the United States one hundred years earlier. I wanted to emphasize that our Museum is more than the building itself. It is an organization which is not confined or defined by its physical boundaries--it could sponsor activities beyond the building itself, and still does. The Museum's Bicentennial activities represented an exciting period, and the impact lingered, leading to new collecting and exhibition activities devoted to U.S. immigration and ethnic history, plus the history of American popular culture, sports, and entertainment. The times were definitely changing for the Museum.

Combine those new initiatives and directions with various long-standing problems of infrastructure and varying approaches to the Museum's philosophy or agenda, and the stage was set for other far-reaching changes. The most fundamental issue, in my estimation, was that the Museum opened to the public in 1964 without its full complement of “permanent” exhibitions. Before construction, spaces had been allocated for exhibit “halls” that would correspond directly to the curatorial units, which had both the responsibility and privilege of making most of the decisions about what would be displayed, with considerable independence. The Division of Ceramics and Glass had its “Hall of Ceramics and Glass” and the Division of Civil Engineering had its “Hall of Civil Engineering,” for example. However, many of these exhibit spaces were undeveloped due to insufficient funds—and many remained empty, year after year. From time to time these spaces were employed for other purposes, and their future grew murky: some of the planned exhibit halls never materialized. That reality, combined with the occasional criticism of the Museum as being confusing to visitors—who didn’t always comprehend the “two museums in one” concept; plus far-reaching philosophical changes in the entire museum world which tended to privilege (as academics like to say) thematic displays over the discipline-specific; plus the already aging infrastructure of the building needing repairs, etc.; plus a sense that the Museum needed changes to revitalize it, eventually led to major architectural modifications as well. These assertions are over-simplifications which omit other significant factors, but they constitute more than I had room to say in my exhibit labels!

One of the consequences of the major re-design of the Museum’s center core was the final removal of what many regarded as the Museum’s signature object, the Foucault pendulum, which was perhaps as symbolically important as the Star-Spangled Banner. Certainly it suggested that the Museum would no longer emphasize science and technology. One might say that the pendulum disappeared incrementally, having been pulled out of the way temporarily for various special programs, then having its cable shortened so it swung on the second floor through a much shorter arc than on the first floor--and eventually vanished, to the dismay of some repeat visitors. Adding a skylight to the center of the building meant that the very popular pendulum was being retired from service, almost certainly forever. The pendulum bob now rests immobile in a glass case in Arthur Molella’s exhibition, “Making a Modern Museum.” See also a related blog by Robert C. Post, "

Fifty Years a Museum." Ironically, there still remains a symbol of science and technology on the Mall side of the Museum—sculptor

Jose de Rivera’s gleaming “Infinity.” Documentation indicates that he was selected precisely to create a work to convey this melding of science, technology, modernity, and art to characterize the Museum.

Developing “my” exhibition was a challenge. Although I was the curator of record, and Russell Cashdollar was the appointed designer, we had lots of help. We had a project manager, Ann Burrola, to keep us on track and on time, but we also had weekly meetings that included other staff, most of whom were stakeholders in the exhibition in some sense. I didn’t always get my way! It was certainly a collaborative effort, and the exhibition would have looked quite different if I had always prevailed. In the first place, I showed far fewer photographs than I had intended because the director of NMAH, John Gray, wanted the images to be large. I have to admit that this constraint did keep the exhibit from being too verbose or text-heavy. If I could have shown the sixty or seventy photographs that I had envisioned, there would have been sixty or seventy explanatory captions that might have overwhelmed the viewer. As I have already indicated, the history of the Museum is complex and multi-faceted, and it really needs a book-length treatment.

![]() |

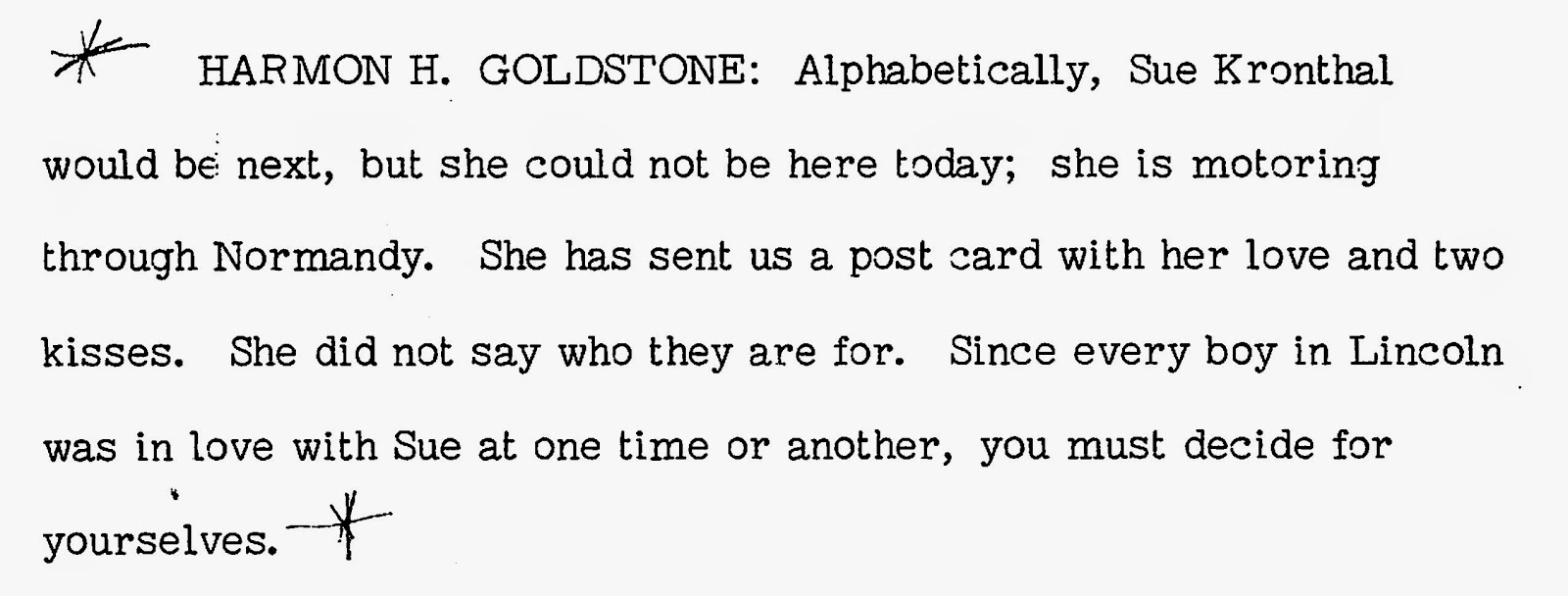

| Colombian dancers demonstrating traditional dance in Museum, ca. 2013. Photographer unidentified. |

I lost one argument on aesthetic grounds, which can be irritating to an art historian, and I have jokingly suggested that I might develop another exhibition, a sort of

“Salon des Refuses” containing the photographs that “they wouldn’t let me show." Other photographs raised debate, but my big surprise was a photograph of a couple performing a traditional Colombian dance in a Museum exhibition space, and I thought it was quite lovely, colorful and exciting. I had wanted to use this image to make two points: the increasing use of public programming in the Museum, including performances, as well as to represent the new emphasis on collecting Latino materials. In meeting after weekly meeting, someone would ask if I couldn’t replace the dance picture with something else, and I demurred, puzzled. Finally I asked point-blank why people objected to this favorite, and someone almost shouted, “Because it’s ugly!” It seemed that people found the male dancer’s position ungainly. I was amazed, but since everyone else agreed, I deleted the photograph, hoping to find a suitable substitute. I never did, so I had to make the two verbal points the picture had represented by squeezing them into other captions where they didn't work as well. (I welcome comments from readers about this photograph!)

![]() |

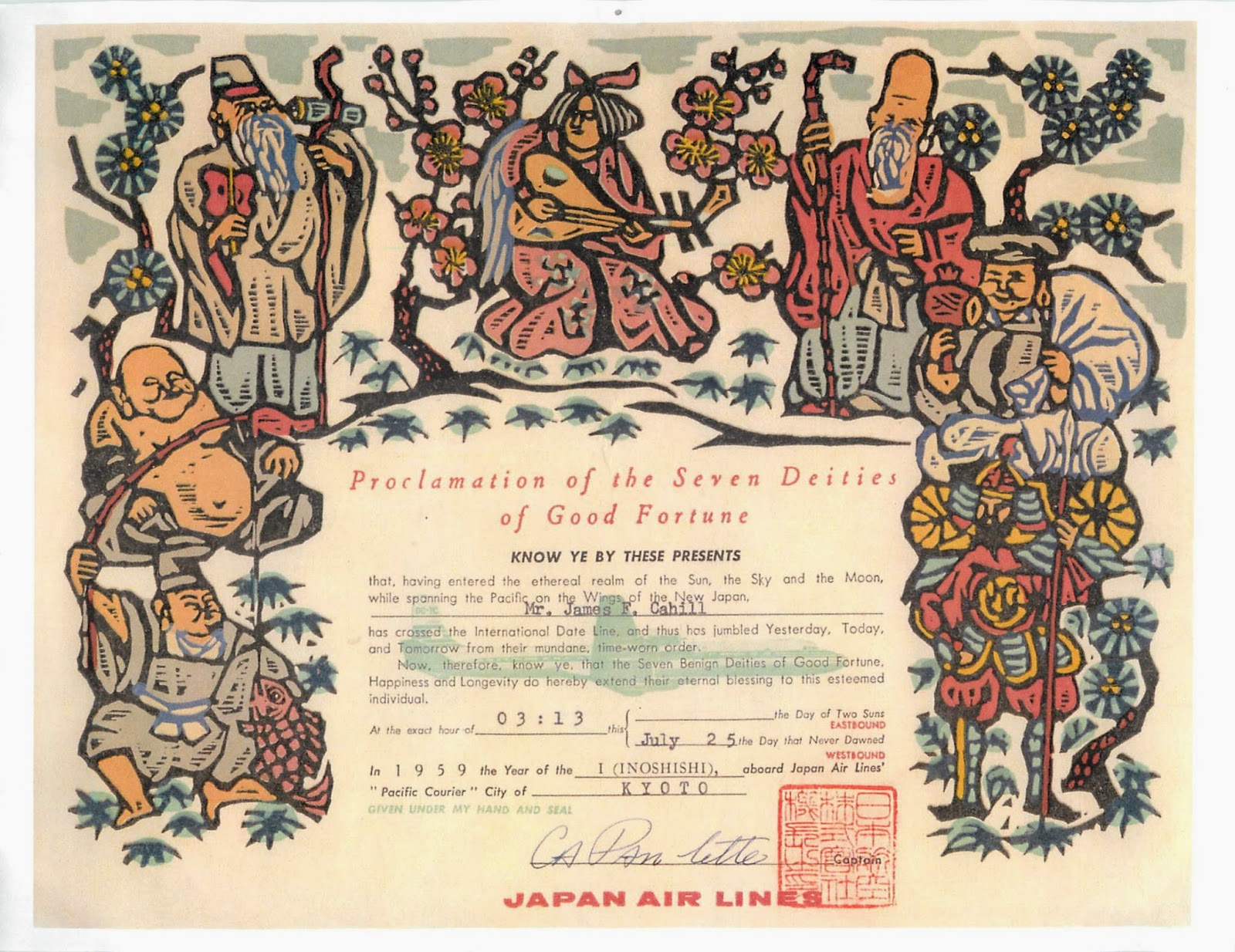

| Actor Joel Grey (left) at the ceremony for his donation of costumes from the musical “Cabaret,” 2013. Photographer unidentified. |

I did succeed, however, in persuading NMAH Director John Gray to allow me to use a picture which he wanted to cut. He objected because he was in the photograph! I told him that I thought it was the most aesthetically satisfying photograph in the show, striking and surrealistic in its juxtaposition of him with actor Joel Grey and strange costume elements between them (the occasion was Joel Grey’s presentation of gifts to the Museum in a public ceremony). At first fearing that I had made a faux pas by suggesting that our director be shown in a humorous, surrealistic composition, I was relieved to find that it was more a question of professional modesty (my over-simplified interpretation). I begged to include it, and his staff helped me convince him. That success balanced my failure to keep the dance photograph in the show. You win some, you lose some!

Another consequence of the work on this exhibition was to make a few corrections in Smithsonian records. I owe Nigel Briggs my gratitude for observing that an SI Archives photograph was mislabeled in the SIRIS catalog entry as depicting the opening reception for the Museum in 1964. The picture had appealed to me not only as a record of the opening, but because it showed a subject which would no longer be deemed appropriate for a museum of “American” history—images and artifacts obviously related to India. Nigel knew that the photograph depicted a traveling exhibition devoted to Jawaharlal Nehru’s India, photographed, organized and designed by the famous husband-wife team of Charles and Ray Eames, and wanted that added to the caption. Closely inspecting the image proved that Nigel was correct, and by conducting simple research, I found that the exhibition opened in the Museum months later, in 1965. It wasn’t a photograph of the opening reception for the Museum—I found nothing suitable—but it still showed the kind of exhibition which could occur in our Museum in the 1960s, but would not in the 2010s, a point which was still useful to make. Pam Henson at SI Archives happily corrected the SIRIS record for

this image.

![]() |

| Traveling exhibition designed by Charles and Ray Eames, titled "Jawaharlal Nehru: His Life and His India," on display at the new Museum of History and Technology, now known as National Museum of American History, from October 26, 1965, to January 2, 1966. Photographer unidentified. Historic Images of the Smithsonian catalog. |

I hope to produce an expanded discussion of the exhibition elsewhere. I’ll admit to having a long history with this Museum myself—no, I wasn’t here for the grand opening, but I arrived not too long afterward. I took on this exhibition project not out of personal nostalgia, but because I thought I had the advantage of useful memories and perspective. As I expected, I also found new information in the process. I was lucky to have SIRIS catalog records and our digital asset management system for image searches, as having to locate all the original negatives or transparencies would have been far more challenging and time-consuming. It was maddening to find enticing pictures in Flickr, however, minus metadata or adequate captioning. Please, always remember the importance of metadata!

David Haberstich

Curator of Photography,

NMAH Archives Center

.jpg)